Protection against social engineering is an extremely important aspect of modern cyber security. Social engineering, based on the manipulation of the human factor, is becoming an increasing threat to organizations and individuals. Fraudsters and attackers use cunning and deceptive methods to gain access to sensitive information, perform phishing attacks, or conduct malicious activities. Effective protection against social engineering involves the adoption of specific security strategies and measures. These include: Awareness: Educating users about basic social engineering techniques, recognizing suspicious activity, and providing security knowledge is the first step in ensuring protection. Strong passwords: Use unique and strong passwords for all accounts and change them periodically to make it harder for attackers. Identity Verification: Be vigilant about giving out personal or financial information.

Verify the authenticity of individuals or organizations that contact you with requests for sensitive data. Beware of links and attachments: Avoid opening unfamiliar or suspicious links and files, as they may contain malware Now that we’ve covered the basics of social engineering and OSINT collection, it’s time to talk about how an organization can minimize the impact of these attacks, or even completely to prevent them. While few people can stop all attacks, you can take steps to reduce the likelihood that an enemy attack will succeed and mitigate its effects if it does occur. This section examines three such methods: awareness programs, reputation monitoring, and incident response. We’ll discuss the elements of a successful awareness program, explain how to implement OSINT monitoring and technical email controls, ensure integration with incident response, and finally perform proactive threat detection.

Alerts are company initiatives designed to provide guidance to users in situations where they encounter or, as is often the case, fall victim to social engineering attacks. These programs are necessary because they allow users to become familiar with the tactics of potential attackers and thereby avoid a potentially negative outcome.

One approach to conducting such training is to inform users about general trends in the security industry. However, it is usually not possible to get by with only general advice. We hope that the previous chapters of this book have helped you understand that traditional security rules, such as looking for a green lock in the address bar of a web browser, and checking the spelling and grammar of emails and link addresses, are no longer enough to prevent phishing attacks. Of course, some novice attackers still make these mistakes. But experienced hackers, who can cause catastrophic damage to the organization, are not prone to such mistakes.

The best approach is to inform users about the specific problems the organization is facing as a result of phishing. For example, if there is a flood of emails from a Nigerian prince or an aggressive business email compromise campaign that sends emails on behalf of a CFO, informing users of the details will help them better resist these attacks. Users are likely to encounter one of these particular attacks, so they should know what to watch out for.

While training should be done frequently to keep users up-to-date on current trends, you also shouldn’t distract them from their direct job responsibilities. Offering awareness activities often enough for users to remember lessons without disrupting work is a delicate balance. I recommend training at least once a quarter. While monthly training sessions provide greater security, they can be burdensome for both users and program administrators.

During this periodic educational event, examples of phishing emails that the organization has received since the last training should be provided. If your organization has done any testing, you can also provide users with statistics and findings similar to those discussed in Chapter 9. The most important thing is to tell users what actions they should take if they receive a phishing email and what to do if will become a victim.

When discussing examples of phishing emails, pay attention to any clues that indicate that the emails are fake. Do it in terms of logic, language and technique. Pay attention to any requests that violate standard operating procedures or reasons. For example, ask why a CFO on vacation in Thailand suddenly needed an accounting department to urgently transfer a few million to a PayPal account and then send a message to Belize. Point out grammatical errors, which could include missing key phrases, different spelling rules, or using the wrong term for employees (partner for Walmart and cast member for Disney). Teach users to hover over a link to see the page the email sends them to. Encourage them to forward suspicious emails to security. Discourage them from sending greetings or responding to suspicious messages without first consulting with security.

One of the main reasons people don’t report falling victim to phishing emails – whether it’s clicking on a link, downloading a malicious file or entering information into a web form – is because they fear punishment or even losing their jobs. But an unreported successful phishing attempt can result in significant downtime or, if an organization is victimized by ransomware, the purchase of huge amounts of bitcoins to decrypt the data.

Employees should know that it is perfectly acceptable and even necessary to report that they have become victims of a social engineering attack. Although they may then be referred for additional training, as a result they will not have to send out their resumes looking for a new job. Many social engineering firms include in the contracts they enter into with their clients, clauses prohibiting the dismissal of employees based on the results of the investigation. As far as I remember, this clause of the contract was not used in court. I have not personally been involved in any litigation regarding this situation, nor do I know anyone who has. Consult an attorney regarding the laws of your country before attempting to include such a clause in your contract.

In rare cases, employees have to be fired because they cannot understand (or are unwilling to follow) key security concepts. Such employees become a burden rather than an asset. However, terminating an employment contract with an employee should be a last resort. Begin by exhausting all efforts to educate the employee, including going beyond the usual awareness programs. Also try to implement additional technical control.

While it’s not in your best interest to punish people for mistakes, it’s helpful to encourage good behavior. However, again, getting it right is a fine art. The reason this issue is sensitive is that sometimes people try to cheat the system.

As an example of how incentives can go wrong, consider what happened to Wells Fargo in 2016. Between 2009 and 2015, Wells Fargo set unattainable sales goals for its employees. He later discovered that those goals led 5,300 employees to create fake Wells Fargo accounts, in some cases for family and friends and in others for complete strangers.

To prevent employees from cheating the system, avoid direct rewards for reporting most phishing attempts. This will trigger employees to intentionally get on phishing lists, creating additional work for the security team. Instead, you can encourage posts about clever or unique phishing emails or something similar – that’s even better. The idea is to encourage messages in general, not the most. If an organization bases rewards on quantity and employees deliberately stage cases, a real phishing attack can end up happening and users become victims; In the meantime, the Security Service will be busy analyzing other emails forwarded to them.

Here are some free or low-cost prizes you can offer:

A gift card to a chain store or coffee shop;

Free parking space for a week;

Participation in the grand prize draw;

Free lunch in the corporate cafe during the week.

To reinforce the correct behavior of employees, offer them a reward in the form of material value. This is social engineering in itself, but it is aimed at achieving positive outcomes for employees and the organization.

Although there is some inconsistency, conducting phishing campaigns as part of your training efforts helps test your employees’ ability to withstand real-world phishing attempts and gauge the response of the organization as a whole.

The first choice you must make when deciding to simulate a phishing campaign is whether to conduct a training attack yourself or hire a third party to do so. To choose the best option for your company, ask yourself how often you plan to hold such events and what your budget is. Outsourced phishing tasks can take anywhere from 4 to 24 hours of billable work per engagement, depending on the desired TOR, scale, and complexity. If you prefer internal testing, you need to find out who will be performing the tasks, what their other responsibilities are, and what impact their preoccupation with the attack will have on your security. If you have the funds to purchase a phishing simulation service from a technology company like Proofpoint, Cofense, or KnowBe4, you can go that route as well.

Reputational and OSINT monitoring

Proactive OSINT monitoring is just as important as proactive social engineering. OSINT monitoring, or the practice of periodically conducting OSINT on yourself or your customers, is also sometimes called brand and reputation monitoring or darknet monitoring. The benefit of OSINT monitoring in any form or variety is that it allows an organization to see what potential attackers can see. This allows the organization to take appropriate action before an attack, whether it’s deleting data if possible, increasing monitoring, or spreading misinformation.

Because OSINT is mostly passively observational in nature, you can’t train users to behave in a way that attackers can’t collect OSINT. In addition, it is very difficult to detect the very fact of collecting OSINT. In many cases, the source of OSINT can be user accounts, and an organization cannot force a user to remove something from a social network unless it violates intellectual property rights under the Digital Copyright Act (DMCA) or any other legal regulation.

When implementing an OSINT monitoring program, focus on finding information that may pose risks to the business. Do not use monitoring as a means of spying or invading employee privacy. One simple way to ensure that your testing remains ethical is to outsource your OSINT monitoring (discussed further in the Outsourcing section).

If your organization decides to implement its own OSINT and reputation monitoring program, it must decide which parameters to rely on and within which framework to work. At the same time, you need to answer the questions “what?”, “when?” and “how to test?”. Since employees can post anything at any time, monthly or quarterly testing is a good solution. Otherwise, many of the considerations required for setting up a phishing campaign apply here. Will the testing be automated or manual? What is your budget? How deep should the interaction be? What coverage? How will you ensure that your employees’ right to privacy and the ability to post on social media are upheld?

Determining the amount of manual testing that needs to be done makes for a more accurate budget estimate. For someone to actively seek OSINT about an organization, that analyst (and possibly the analyst’s employer) must be paid. Automated services do not require this, but the owner may charge a fee for using the service.

Define a research scope similar to that used for social engineering tasks. This is necessary in order not to violate the privacy of your employees. While an organization should be concerned about what information suppliers, employees, contractors, visitors, and partners share with the public, avoid searching for content that employees share privately with each other or with friends. Don’t have them contact you on social media or try to join your friend lists using fake accounts.

In my experience, it is often better to outsource OSINT and reputation monitoring to a third party. When third parties collect OSINT data about your employees, you can eliminate the fear that the organization is spying on employees. It also keeps your organization’s security team away from personal accounts belonging to other employees, reducing the likelihood of accusations of harassment or extortion. Finally, it prevents abuse under the guise of security.

In addition to preventing extortion claims, involving third parties in conducting OSINT monitoring allows investigators to operate with minimal bias.

They act more like a sieve than a pump, which means they filter out extraneous non-security information, often by automated web scanners, without any intent, and only provide the organization with relevant information.

Responding to incidents

Incident response is a set of predetermined actions that an organization will take if an adverse event meets the criteria to classify it as an incident. Part of preparing for incident response is thinking about what might happen if social engineering is successful. The rest is about studying interactions within your company so that you can take steps to prevent a large-scale or catastrophic impact. As I have argued earlier in this book, decisions about what action to take should not be made in the midst of an active social engineering campaign.

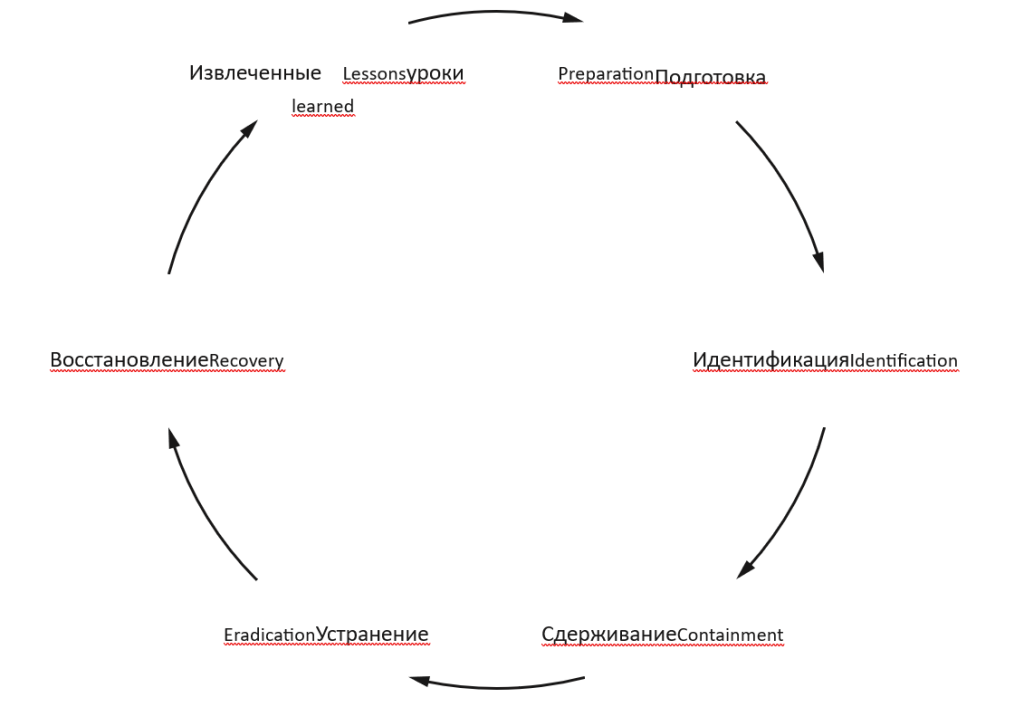

The SANS Institute, a security research and training organization, defines a holistic incident response process that includes preparation, identification, containment, remediation, recovery, and lessons learned (Figure 10.1). This incident response standard, also known as PICERL (Preparation, Identification, Containment, Eradication, Recovery, Lessons Learned), takes into account the entire life cycle of an incident, starting with its classification and ending with analysis after its resolution. At each stage, you determine the steps necessary to minimize the impact of the attack, restore services as quickly as possible, and eliminate the root cause of the event.

In the preparation phase, which often grows out of the learning phase from a previous incident, you anticipate future incidents by running awareness programs, running phishing simulations, and monitoring your OSINT.

The identification phase begins when the organization becomes aware of an event that the organization classifies as an incident. In the context of social engineering, this phase can be triggered, for example, by the following events: the user reported going through a phishing link; the user reported that he provided information to the subscriber by phone; Ransomware alerts from anti-malware tools. Server logs indicating Scan ports, have extremely high access, or download all public files. any email received at a Lure email address (which serves no other purpose than to be detected by malicious search engines); suspicious email alerts from email filtering software such as Proofpoint or Mimecast; Customizable alerts based on information about internal and external threats.

Once an incident has been identified and classified, you move to the containment phase, where you take steps to prevent further spread of the threat. When it comes to social engineering, containment actions can include blocking a domain in the corporate DNS or removing email from the mail server and queue. You can also directly block access to a domain, IP address, or email address from the Organization’s network and systems. Finally, you can isolate or sandbox a suspect computer from the rest of the network, force a user’s password reset, or even deactivate affected user accounts. Once you’ve taken the first steps, you need to send your users a mass email campaign so they don’t fall victim.

In the elimination stage, you solve the problem. Remove any previously installed malware. You then analyze the root cause of the incident and begin to identify actions that will help you recover. Unless malware is involved, this is usually a very short phase.

In the recovery phase, you take all necessary steps to fully recover from the incident. This may include re-enabling user accounts, changing the network configuration to remove sandboxes or other segregations applied by malicious activity, and undoing changes made by the attacker.

Once everything is back to normal, in the lesson learning phase, you re-analyze the root cause of the incident to identify existing gaps in your knowledge and actions. Then move on to the phase of closing these gaps in the preparation phase. This is the time to think and decide what could be done better.

Now that you know the basics of incident response, you need to determine what users should do if they fall victim to various types of social engineering attacks. Let’s start with phishing. A phishing email that contains links or files can allow an attacker to gain access to your systems. So your goal should be to accelerate containment and eradication.

One tip for quickly responding to an attack is to choose one bright color for all network cables connected to employee computers. This will allow employees to be instructed to disconnect this colored cable from the back of the computer or outlet in any suspicious situation. Remember that some computers may be connected to a wireless network, so you should also define the behavior of turning off wireless devices.

Ask users to provide an approximate time when the incident occurred. This detail helps the security team quickly find the logs they need to review, rather than leaving them without clues as to where to look. After becoming a victim of an attack, users must log off, turn off the power, disconnect from the network, or put their system to sleep. The actions that the user must take depend on the capabilities of the organization and its potential response to the incident. Also, if an organization is going to restore a system from known safe media, the correct course of action may be to simply shut down the system after collecting artifacts that indicate an attacker attack.

The user must also report the original email address or phishing website, any windows and applications that were open, and whether anything unusual happened on the screen.

You should print these guidelines, laminate them, and post them at each user’s physical workplace. At any time, the user must be able to view the list and perform the necessary actions.

Although vishing is similar to phishing, it presents a unique problem. In the absence of control over all telephone calls, the ability to identify and answer calls depends on the employees who report them, as well as knowing the actions that must be taken in advance. No widespread or accurate intrusion detection systems (IDS) or SEIMs cover phone calls. Companies can monitor the Internet traffic of any IP phones connected to the corporate Wi-Fi network, but not the normal phone calls or their context.

Fortunately, an attacker cannot directly log in and hijack a network with a phone call.

Even if an attacker obtains the necessary information through vishing, technical controls can prevent further damage. In either case, you must define actions to respond to phishing attempts.

First, if users suspect phishing, they should either ask to call back and hang up, try to get information from the caller, or lie to confuse them. The organization’s security team will need to decide what actions to train employees on. By encouraging users to ask counter-questions or lie, you run the risk that an inexperienced user may inadvertently reveal valuable and accurate information. In any case, users should contact the data protection team and provide the approximate time the incident occurred, any actions they took, the caller’s phone number, the information they were able to obtain, and the information they provided to the scammer . They must also inform the caller of their accent, dialect, tone or mood, or the presence of background noise.

Discovering an OSINT collection is difficult because platforms such as Shodan, Censys, and Have I Been Pwned do not allow you to automatically issue search alerts, although you can write your own code to issue alerts whenever an organization’s data appears on such platforms. Have I Been Pwned allows organizations that can verify ownership of a domain to set such alerts, but will not share compromised credentials belonging to accounts on the domain. But because OSINT collection usually occurs during the investigation phase of ethical hacking, it is often accompanied by scans of easily detectable network resources.

The first level of detection is a content delivery system (CDN) such as Cloudflare or Amazon CloudFront, if used. The next level is in the web server logs or web application logs. These sources will inform the organization about who is scanning and what is being scanned. Often these alerts lack the context necessary to distinguish between mass web crawls and the actions of a real adversary trying to gather OSINT or working through resource scans.

Decide which actions should be blocked. Examples include blocking users after a certain number of 404 errors caused by a site crawl; blocking or limiting the search speed to a certain number of events per second; Block anyone who downloads a certain number of public files using a certain user-agent string in a browser or script. and blocking users who go to a special trap page.

Depending on the severity of the attack, the notoriety it receives, and other events occurring in the news field, members of the media may try to speak to people in your organization during the incident. While it shouldn’t be your top priority, failing to respond to media calls can have worse consequences than simply admitting you don’t know all the details at this point. Although the media should contact the organization’s public relations department, some journalists may try to interview any employee.

To control the message communicated to the public, prohibit communication with the media for all employees except those identified in your incident response plan. Provide third-party staff with a response template to handle such requests. This can be as simple as “I am not authorized to discuss the subject of your request” or a referral to the company’s official public relations officer.

Employees authorized to speak to the media must understand what tone to use, how to decline to answer, and who to talk to in order to learn the facts they will share with reporters. Also designate a person or group to review and approve any communications the public relations officer will make to the media.

I also strongly recommend consulting with your organization’s internal public relations team and any outside consultants your organization uses. They will be able to talk about your organization’s specific policies and procedures, while I talk about more general principles.

If you don’t explain to users how they should report suspicious incidents, they may report the problem to a security guard at a checkpoint who doesn’t have the authority to deal with such issues. One strategy is to create a phishing@ organization.com email to collect phishing emails that users receive. You can also configure fields with [email protected] or [email protected] as general addresses that forward emails to the desired recipients.

If the user has been a victim of phishing and possibly introduced malware into the environment, an email notification may not be the best solution. This is because the entire email system can be compromised and attackers can read, block or modify messages. Depending on the size of the organization and whether the user is on-site or remote, you can ask to report the incident in person, make a phone call, or send a message in a private chat or secure text messaging platform.

If a phishing email is detected, the security team must analyze the email and any relevant information about it in accordance with organizational policies and procedures. This will be useful for gathering threat intelligence based on the industry the organization operates in and whether it is associated with any clearing house and intelligence center.

From the email itself, you should get the original email address, details about whether the email address was spoofed (discussed in Chapter 12), and the sender’s IP address. You should also block addresses and referrer addresses and check logs to see if other users or hosts have contacted those addresses. Use the tools described in Chapter 12 to further analyze the attack.

If the phishing scheme involves sending a malicious file, it can be uploaded to the VirusTotal malware detection website to get a quick response about the contents of the file if the malware is known. Also, take the cryptographic hash of the file and check systems on the local network for files that produce the same hash. Configure SEIM to also notify you of incoming instances of such a file.

Capture any IP addresses or URLs associated with the phishing email to redirect users to a secure page and set up alerts on workstations for those trying to access the malicious site. Once an email is hidden, the security team can contact all users advising them to avoid the malicious email.

When incident response moves into the recovery phase, transfer the collected information to the threat intelligence service and follow your organization’s guidelines for publishing and distributing information to users.

We used materials from the book “Social Engineering and Ethical Hacking in Practice”, which was written by Joe Gray.