According to thousands of pages of confidential corporate documents, Russian intelligence services worked with a Moscow-based defense contractor to boost its ability to carry out cyberattacks, spread disinformation and monitor sections of the Internet. The documents detail a set of computer programs and databases that will allow Russian intelligence services and hacking groups to better find vulnerabilities, coordinate attacks and monitor online activity. The documents show the firm supported operations including both disinformation on social media and training to remotely detonate real-world targets such as naval, air and rail control systems. Anonymous provided a German journalist with documents from the contractor, NTC Vulkan, after expressing outrage at Russia’s attack on Ukraine. The leak, an unusual case for Russia’s secretive military-industrial complex, demonstrates another unintended consequence of President Vladimir Putin’s decision to drag his country into war. Officials from five Western intelligence agencies and several independent cybersecurity companies said they believed the documents to be authentic after reviewing excerpts at the request of The Washington Post and several partner news organizations.

Those officials and experts were unable to find conclusive evidence that the systems were deployed by Russia or used in specific cyberattacks, but the documents describe testing and payment for work done by Vulkan for Russian security services and several related research institutes. The company has both government and civilian clients. The Treasury offers a rare window into the secretive corporate affairs of Russia’s military and spy agencies, including working for the infamous government hacking group Sandworm. US officials have accused Sandworm of causing two blackouts in Ukraine, disrupting the opening ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics and launching NotPetya, the most economically devastating malware in history. (7 Findings from the Vulkan Files Investigation)

One of the leaked documents mentions the military intelligence unit Sandworm’s digital designation, 74455, suggesting that Vulkan was preparing software for use by an elite hacking squad. The unsigned 11-page document, dated 2019, showed a Sandworm official endorsing a data transfer protocol for one of the platforms. “The company is doing bad things, and the Russian government is cowardly and wrong,” the person who provided the documents to a German reporter said shortly after the invasion of Ukraine. The reporter then shared them with a consortium of news organizations that includes The Washington Post and is led by Paper Trail Media and Der Spiegel, both based in Germany. An anonymous person who spoke to the reporter via an encrypted chat app declined to be identified before ending contact, saying he needed to disappear “like a ghost” for security reasons.

“I’m angry because of the invasion of Ukraine and the terrible things that are happening there,” the man said. “I hope you can use this information to show what goes on behind closed doors.”

Vulkan did not respond to requests for comment. A company employee who answered the phone at head office confirmed that an email with inquiries had been received and said it would be responded to by company officials “if they are interested.” No answers were received. Kremlin officials also did not respond to requests for comment. The cache of more than 5,000 pages of documents, dated between 2016 and 2021, includes manuals, specifications and other details of software developed by Vulkan for the Russian military and intelligence. It also contains internal company emails, financial records and contracts that demonstrate both the ambition of Russian cyber operations and the extent of work that Moscow has outsourced. This includes programs to create fake social media pages and software that can identify and accumulate lists of vulnerabilities in computer systems around the world for a possible future attack. Several user interface mockups for the project, known as Amezit, appear to depict examples of possible targets for the hackers, including the Foreign Ministry in Switzerland and a nuclear power plant in that country. Another document shows a map of the United States with circles that appear to represent clusters of Internet servers.

One artwork for the Vulkan platform, called Skan, references an area in the US labeled “Fairfield” as a location to look for network vulnerabilities to exploit in an attack. Another document describes a “user scenario” in which hacking groups would identify vulnerable routers in North Korea, presumably for potential use in a cyber attack. However, the documents do not contain verified lists of targets, malicious software code, or evidence linking the projects to known cyberattacks. Still, they offer insight into the goals of a Russian state that — like other major powers, including the United States — is seeking to develop and systematize its ability to launch cyberattacks with greater speed, scale, and effectiveness. “These documents show that Russia views attacks on civilian critical infrastructure and manipulation of social media as the same mission, which is essentially an attack on the enemy’s will,” said John Hultquist, vice president of intelligence analysis at cyber security company. Mandiant who reviewed selected documents at the request of The Post and its partners.

The role of contractors in Russian cyberwarfare is “very important,” especially for Russian military intelligence, commonly known as the GRU, said a Western intelligence analyst who spoke on condition of anonymity to share confidential findings. “They are an important pillar of offensive cyber research and development of the GRU. They provide expert knowledge that the GRU may lack on a certain issue. Intelligence services can conduct cyber operations without them, but probably not as well.” Three former Vulkan employees, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution, confirmed some details about the company. Vulkan’s financial records, which have been separately obtained by news organizations, match references in documents in several cases detailing multimillion-dollar transactions between known Russian military or intelligence agencies and the company. Intelligence and cybersecurity experts said details in the documents also match information gathered about Russian hacking programs — including a smaller, earlier leak — and appear to describe new tools for conducting offensive cyber operations. Vulkan is one of dozens of private firms known to provide specialized cyber software to Russian security services, they said.

Experts cautioned that it is not known which of the programs were completed and deployed, rather than just designed and ordered by the Russian military, particularly units linked to the GRU. However, the documents refer to government-mandated testing, customer-requested changes, and finished projects, strongly suggesting that at least trial versions of some programs have been activated. “Similar network diagrams and project documents can be found infrequently. This is really a very confusing thing. It was not intended for public display,” one Western intelligence official said on condition of anonymity to share a candid assessment of the classified findings. “But it makes sense to pay attention. Because you better understand what the GRU is trying to do.” Google’s Threat Analysis Group, the tech company’s top cyber threat hunter, found evidence in 2012 that Vulkan was being used by the SVR, Russia’s foreign intelligence service. The researchers observed a suspicious test phishing email being sent from a Gmail account to a Vulkan email account that was created by the same person, apparently an employee of the company. “Using test messages is a common practice to test phishing emails before they are used,” Google said in a statement. Following this test email, Google analysts saw the same Gmail address being used to send malware known to use SVR against other targets.

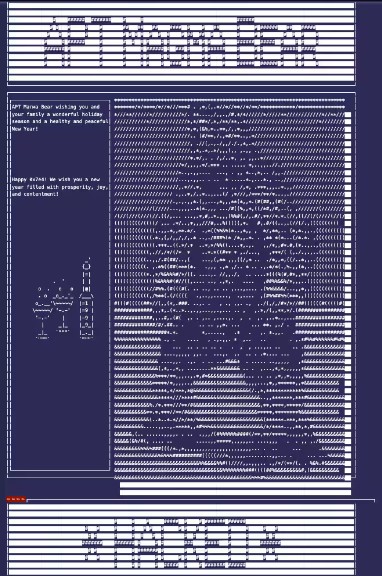

It was “not the smartest move” by a Vulkan employee, said one Google analyst, speaking on condition of anonymity to describe the confidential findings. “It was definitely a mistake.” Mentions of the company can also be found on VirusTotal, Google’s malware database service that is a resource for security researchers. A file labeled “Secret Party NTC Vulkan” is a party invitation disguised as malware that usually controls the user’s computer. The invitation — innocuous on the surface — automatically loads an illustration of a big bear next to a bottle of champagne and two glasses.

The image is labeled “APT Magma Bear,” a reference to how Western cybersecurity officials codenamed Russian hacking groups ursine. APT refers to “Advanced Persistent Threat,” a cybersecurity term for the most serious hacking groups, usually run by countries like Russia. The invitation reads, “APT Magma Bear wishes you and your family wonderful holidays and a healthy and peaceful New Year!” Soviet military music plays in the background.

Vulkan was founded in 2010 and has about 135 employees, according to Russian business information websites. The company’s website states that its head office is located in the northeast of Moscow. A promotional video on the company’s website portrays Vulkan as a disruptive technology startup that “solves corporate problems” and has a “comfortable work environment.” It ends with the statement that Vulcan’s goal is to “make the world a better place.” The commercial does not mention military or intelligence work. “The work brought pleasure. We used the latest technology,” one former employee said in an interview on the condition of anonymity because of fear of punishment. “People were really smart. And the money was good.” Some former Vulkan employees later went on to work for major Western companies, including Amazon and Siemens.

Both companies released statements in which they did not deny that the former Vulkan employees worked for them, but they said that internal corporate controls protect against unauthorized access to sensitive data. The documents also show that Vulkan intended to use a range of American equipment to configure systems for Russian security services. The design documents repeatedly mention American products, including Intel processors and Cisco routers, which are to be used to configure the “hardware and software” systems of Russian military and intelligence units.

There are other connections with American companies. Some of those companies, including IBM, Boeing and Dell, have at one time worked with Vulkan, according to its website, which describes commercial software development work with no apparent connection to intelligence or hacking operations. Representatives of IBM, Boeing and Dell did not deny that these organizations had previously worked with Vulkan, but said that they currently have no business relationship with the company.

He first shared the treasure trove of documents with a reporter from the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. The consortium examining the documents consists of 11 members, including The Post, The Guardian, Le Monde, Der Spiegel, iStories, Paper Trail Media and Süddeutsche Zeitung, from eight countries. Among the thousands of pages of leaked Vulkan documents are projects designed to automate and secure the operations of Russian hacking units. Amezit, for example, details the automation tactic of creating massive numbers of fake social media accounts for disinformation campaigns. One cache leak document describes how to use banks of mobile phone SIM cards to defeat verification of new accounts on Facebook, Twitter and other social networks. Reporters from Le Monde, Der Spiegel and Paper Trail Media, working with the Twitter accounts listed in the documents, found evidence that the tools were likely used for multiple disinformation campaigns in several countries. One effort involved tweets in 2016 — when Russian disinformation operatives were working to bolster Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump and undermine Democrat Hillary Clinton — linking to a website that claimed Clinton had made a “desperate attempt” to “restore its leadership position”, seeking foreign support. in Italy. Journalists also found evidence of software being used to create fake social media accounts in Russia and abroad to push narratives in line with official state propaganda, including denials that Russian attacks in Syria have resulted in civilian deaths.

According to the documents, Amezit also has other features that would allow Russian officials to monitor, filter and monitor sections of the Internet in regions they control. They suggest that the program contains tools that shape what Internet users will see on social media. The project is repeatedly described in the documents as a complex of systems of “informational limitation of the local territory” and the creation of an “autonomous segment of the data transmission network.” A 2017 draft manual for one of Amezit’s systems includes instructions for “preparing, posting and promoting special materials” — most likely propaganda spread via fake social media accounts, phone calls, emails and text messages.

One mockup in a 2016 design document allows a user to hover over an object on a map and display IP addresses, domain names, and operating systems, as well as other information about “physical objects.” One such physical facility, highlighted in fluorescent green, is the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Bern, Switzerland, which shows a hypothetical email address and “target of attack” to “obtain root privileges.” Another facility highlighted on the map is the Muhleberg nuclear power plant, west of Bern. It stopped producing electricity in 2019.

One mockup in a 2016 design document allows a user to hover over an object on a map and display IP addresses, domain names, and operating systems, as well as other information about “physical objects.”

One such physical facility, highlighted in fluorescent green, is the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Bern, Switzerland, which shows a hypothetical email address and “target of attack” to “obtain root privileges.” Another facility highlighted on the map is the Muhleberg nuclear power plant, west of Bern. It stopped producing electricity in 2019.

Dmytro Alperovych, who co-founded cyber threat intelligence firm CrowdStrike, said the documents indicate that Amezit is designed to detect and map critical objects such as railways and power plants, but only when an attacker has physical access to the object. object “With physical access, you can plug this tool into a network and it will map out vulnerable machines,” said Alperovitch, now chairman of the Silverado Policy Accelerator, a think tank in Washington. The emails suggest that Amezit systems were at least tested by Russian intelligence until 2020. The company’s e-mail dated May 16, 2019 describes the feedback from the client and the desire to change the program. The spreadsheet indicates which parts of the project have been completed.

The document also claims that in 2018, Vulkan was contracted to create a training program called Crystal-2 to allow up to 30 trainees to work simultaneously. The document mentions testing of “the Amezit system for disabling [disabling] rail, air, and maritime transport control systems,” but does not specify whether the training program envisioned in the documents was carried out. The trainees will also “test methods of obtaining unauthorized access to local computer and technological networks of infrastructure and facilities for life support in populated areas and industrial zones,” potentially using the capabilities that the document attributes to Amezit. The document further states: “The level of secrecy of the information processed and stored in the product is ‘Top Secret’.”

Skan, another major project described in the documents, allowed Russian attackers to continuously scan the Internet for vulnerable systems and compile them into a database for possible future attacks. Joe Slovik, manager of threat analysis at cybersecurity firm Huntress, said Skan was likely designed to work in tandem with other software. “It’s a back-end system that would allow all of that — organizing and potentially assigning tasks and targeting opportunities in a way that can be centrally managed,” he said. Slovik said Sandworm, the Russian military hacking group blamed for numerous hacking attacks, would likely want to keep a large repository of vulnerabilities. A 2019 paper says Skan can be used to display “a list of all possible attack scenarios” and highlight all nodes on a network that could be involved in attacks. According to the released documents, the system also provides coordination between Russian hacking units, allowing “data to be shared between potential geographically dispersed special forces.” “Skan reminds me of old war movies where people stand … and place their artillery and troops on a map,” says Gabby Roncone, another cybersecurity expert at Mandiant. “And then they want to understand where the enemy tanks are and where they need to hit first to break through the enemy lines.” There is evidence that at least part of the “Scan” was supplied by the Russian military. In an email dated May 27, 2020, Vulkan developer Oleg Nikitin described gathering a list of employees “to visit our functional user’s area” to install and configure hardware for the Skan project, as well as update and configure software and demonstrate functionality. The featured user is described as “Khimki”, meaning the Moscow suburb where Sandworm is based. “The territory is closed, the regime is strict,” wrote Nikitin, using Russian terms for a guarded secret state facility. Nikitin did not respond to a request for comment. Maria Kristof of Paper Trail Media contributed to this report. Craig Timberg is The Post’s senior investigative editor and former technology reporter. Ellen Nakashima is a Post national security reporter who has written on cybersecurity and intelligence issues. Hannes Münzinger and Hakan Tanriverdi are senior investigative reporters at Paper Trail Media in Munich. Münzinger obtained the trove of documents and had his first conversations with the source while working for his previous employer, the Süddeutsche Zeitung.